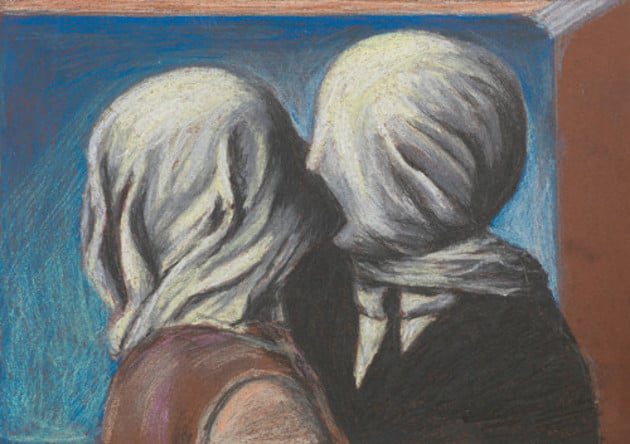

Occasionally, our relationships need to get re-started. We love one another but a lot has accumulated that we haven't properly dealt with. Certain things haven't been said, resentments may have built up, playfulness has been neglected and there is a lot we should - but haven't found the words - to express.

So we've drawn up a set of some of the most important questions that a couple might discuss together in order to reopen channels of feeling and communication.

The questions - and the supporting micro-essays - invite candour, confession and radical openness. As we answer them, it's centrally important to maintain an atmosphere of extreme kindness and calm, without any hint of moralism or bitterness.

Often, we give up on each other too soon. Relationships that, with the right assistance, might have been good enough (or even more than that) come unstuck because we don't work out how to speak about and listen to what is really on our minds. This is a tool with which to try to save love.

1. The things I would like to be appreciated for...

This definitely isn't the moment to be vindictive or self-pitying. Being taken rather for granted is pretty much unavoidable in any established relationship.

At the same time, it's crucial to be able to drain the potential lake of bitterness by communicating what we do feel we contribute and are good at. We naturally long for our partner to notice and like the things we like about ourselves.

At the start of the relationship, what was decent about both of us was automatically very obvious. Then, with time, we got spoilt. It's a natural way our minds work: if we lived in the Alhambra palace, pretty soon we wouldn't even notice the tile work.

We're not asking for adulation. Our flaws are beyond doubt. We just need our compensating merits to be given a bit more weight once in awhile. We won't mind being criticised or corrected quite so much if we feel that, every now and then, the other person has properly grasped our upsides as well. A burst of appreciation will embolden both of us for the more critical moments ahead.

2. Where I'm unfulfilled in my life...

Often we don't say at all clearly what's missing from our lives outside the relationship. Maybe we're disappointed that our social scene isn't more exciting; perhaps we're yearning to travel; it could be something around money or how much time we have to give to work or our parents. It doesn't matter how unreasonable or trivial these things sound; the point is that they're important to us and they're not going right.

As a result, we have tendencies to get grumpy, depressed, angry or agitated. However, day to day, we tend not to explain the origins of our moods very well. Our partner is the witness to distress but can't easily recognise where it is coming from. So they make the next most obvious move: they assume we're simply mean or bad tempered.

This is a chance to explain the background dissatisfactions responsible for some of our most acute day-to-day irritations and withdrawn states; a chance to demonstrate that we are almost always sad and anxious, not simply mean or bad.

3. When I'm upset, I need you to comfort me like this...

Often enough, we get stuck in a poignant impasse: our partner wants to help us, but the way they go about offering assistance irritates us or can't soothe us. We feel neglected, and yet at the same time, our partner concludes that their well-meaning efforts are being received ungratefully.

This is a chance to consider how both of you characteristically try to help each other - and how you would perhaps ideally like to be helped when there is difficulty in your lives.

We might find that if a partner starts to cook for us and takes care of practical matters, we feel they are avoiding the real issues and are being lazy where it counts. Or we might find that being told 'it will all be OK' is deeply unnerving. Or it might be exactly what we want to hear. We might find agreement ('yes, it is all very difficult, it's awful, so bad') hugely useful. Or terrifying. We might much feel that an action - being hugged or invited to lie down for a while - is essential, or patronising at just the wrong moment.

The point is: we need to explain what works for us and hear what works for the other. Once we've got a clearer sense of how we each want comfort to be effectively delivered, we can try to adjust our style in order actually to be - rather than merely want to be - nice.

4. When I'm in a panic, I...

It's an occasion to explain our pattern of reaction. We're not trying to justify it. We're not saying we think this is the ideal or a lovely way to react. We're just - as a starter - admitting that we ourselves recognise certain tendencies in our own nature and are trying to explain what they are.

Maybe our instinct - when we feel under threat - is to react by getting very controlling. Perhaps we burst into tears and announce that everything is hopeless (drowning a specific agitation in an ocean of woe). Perhaps we turn to a particularly cutting type of sarcasm, or maybe we lash out verbally and say quite horrible things. Or we feel we have to be on our own and go deadly silent.

What we're doing here is helping our partner to interpret what are - outwardly - some very disconcerting bits of behaviour. We're asking them to see these not as reflections of the whole of our nature, but as ways we try to cope with situations that come across as especially threatening to us.

We're trying to put together our own - inevitably very strange - translation manual. We're trying to make some of the least lovable bits of our own behaviour seem less alarming and a little more forgivable.

5. I'd probably be more normal if the following hadn't happened to me in childhood...

It's hugely helpful for there to be a recognition in the couple that both parties are - of course - a little crazy in a variety of ways. This isn't a personal failing, it's just how all human beings are. No one ever quite reaches settled, mature and sane adulthood.

The problems almost always start in childhood. This question should provide a calm moment to explain a little more about what happened when we were little - and to lay out why it may today make us, at points, unnaturally intense and hard to live with.

Perhaps there was a very punitive parent, so we've grown up prone to lying about things that are awkward. Or someone was a bit depressed and we had to be entirely cheerful and now have a tendency to be deaf to bad news. Maybe a parent disappointed us badly, and we aren't nowadays very good at trust and the business of letting our guard down.

A knowledge of intimate histories shifts our ideas of what the other person is doing, when they are annoying or disappointing. They're not just being difficult - they are struggling with the complex legacy of a past we still don't know enough about, just as they don't know enough about ours.

6. What I find annoying about you is...

It sounds like a nasty theme - but, when handled correctly, it is the gateway to greater tenderness and self-development.

Everyone is radically flawed. So naturally, two people in a relationship will always be trying to teach each other how to be better versions of themselves. They'll be trying to get the other person to be, for example, more punctual, less cold, more contained, less impulsive, more thoughtful...

It's sometimes said that true love means accepting someone just as they are. But in reality, this can't be true or indeed wise. We should want to be taught - and to teach. The issue is how we go about the emotional pedagogical business.

When we are in the teaching role, we need to proceed with immense sympathy and tact - and when we are in the listening (or pupil) role, we need to bravely accept that someone can have a legitimate criticism of us and yet still want the best for us.

This is an opportunity to do something very rare: level criticism without anger. And it's a chance to hear criticism as more than an attack, to interpret it for what it may truly be: a desire to help us to grow.

7. I guess I'm difficult to live with because...

We don't need people to be perfect. What we need - above all - is a sense that they understand their imperfections, that they are ready to explain them to us, and that they can do so outside of the moments when they have hurt us.

It's a sign of being a grown up that we can, finally, admit that we are monstrously difficult to live with. Everyone is. It's just a question of how we, in particular, are tricky.

We might, for instance, have very strong views about interior design and find any opposition to our taste quite distressing. We might be fanatically (and often anxiously) devoted to our work. We could have strong views on how long it is OK to keep a taxi waiting, whether bedroom windows should be kept open at night or what time a child needs to go to bed (to start sketching a potentially endless list).

Recognising where we are inflexible and where we are very demanding won't solve all the points of contention. But it can hugely and decisively change the atmosphere. We should both never be done with the business of apologising for how tricky we are to be around.

8.__What I would like to be forgiven for...

No relationship could survive long without forgiveness. We know we're in need of forgiveness, but - tragically - we're often especially stubborn (in the moment) about things that we need the other person to be generous about.

Most of the time, we tell ourselves that we're not to blame; that it's our partner who should be apologising and asking us to forgive them. But in our most honest moments (perhaps at 3am, when it's very quiet and there's a full moon outside), we do sometimes recognise that we have brought certain troubles into our partner's life. It would be strange if we hadn't. We're complex individuals; we're not remotely perfect in every way. We know we've let them down badly in certain areas...

Unfortunately, when we feel guilty - but are unforgiven - we have a tendency to get more aggressive and in denial about what we've done.

We therefore need to create an atmosphere where an admission of guilt will be met with tolerance and sympathy. We're not at this moment asking the other person to wipe the slate clean. We're just stating something from our own side: that we would like to be forgiven for certain things - which, we admit, we're actually really sorry about. We're going to try to do better - if we're given the chance.

9. Where I'd love you to realise you hurt me is...

We're carrying around wounds that we have found it, understandably and inevitably, hard to articulate. Perhaps the complaints sounded too petty or humiliating to mention at the time. The problem is that when they fester, the current of affection starts to get blocked - and soon, we may find ourselves flinching when the partner tries to touch us or suggests we make love. What we call 'loss of desire' (or more plainly 'going off sex') is usually simply a kind of anger with a partner that hasn't had a chance to understand itself.

This is safe moment in which to reveal some of these - typically entirely unintentional - hurts. Maybe last month there was something around work, or their mother, or the way they responded to a fairly innocent enquiry in the kitchen before work.

It's vital that the partner doesn't step in and deny that the hurt took place or start to move the blame back or indeed remark that the hurt is too small to take seriously.

There is no such thing as a hurt that is too small. If it was felt, it is legitimate.

What matters is that each person can be heard and can lay out areas where the other wounded them more than they've to date been able to explain.

This exercise shouldn't reignite problems. It should help solve them once and for all - and should be repeated regularly, as often as once a week.

10. A slightly weird thing about me around sex is...

None of us are entirely normal about sex. And yet the pressure to be normal is seldom greater than in the bedroom. At precisely the moment when we long to be intimate, we're terrified that we'll come across as perverted, dirty, stunted or degenerate.

The result is that we start to lie. We shut off areas of interest. We conceal what we really want. And so we go off sex altogether or develop a fantasy life from which the partner is wholly excluded.

It's key, therefore, to create a nurturing environment of total acceptance around our sexual imaginations. Nothing should be off-limits. The strangest, most off-beat fantasies should be allowed to be discussed in an atmosphere of mutual tolerance and love. We should accept that there is - of course - a deep difference between a fantasy and a desire for it to be acted out. Fantasising about a role play is quite different from actually doing it.

We grow apart from a misplaced sense of propriety. We try to be 'good' where we shouldn't. Now is the time to admit to our interestingly dark sides. We might say things like: when I was fourteen there was this person who I saw wearing this kind of top... Or: I feel that if someone is shouting at me, then they must be really interested in me. Or: I feel that sex is very bad, so I need to be told I am very bad before I can really enjoy it.

The whole point of sex is to be liberated from the rules and demands of ordinary life. It's meant to be naughty and, if it's going well, even perhaps a bit sick-sounding.

11. As an alternative to actual intercourse, I'd be excited if we could...

There's a lot of pressure to perform well around sex. But the reality of relationships means that we might have ended up not in the right frame of mind to perform well in the bedroom. This can create a lot of pressure, and then guilt and resentment. It's easy for one or both partners to think that the explanation must be a loss of love.

A useful move, especially on a weekend away or a special night in, is to take the pressure off high performance sex. We should both accept that, for a while at any rate, it will be better to explore areas of erotic life where the expectations are lower - but where there is still a genuine degree of sensual connection.

For instance, you might really like having the the nape of your neck caressed, or the upper part of your arm stroked very gently, with just the tip of the fingers. You might love having someone play with your hair or hug you tightly in the pitch darkness. You might want to be watched by a partner from the other side of the room or to look at something online together.

The point isn't to stop intercourse forever, it's to get back in the mood very gradually, without demands - and with a sense of imagination and mutual discovery.

12. My fantasies are....

On the face of it, it sounds weird: how can you two have been together for so long and not know each other's sexual fantasies? But a lot may have happened since you first met and shared such thoughts. You may have got mired in practical issues and lost touch with each other's more intimate sides.

Talking about fantasies is - we should admit from the start - a very vulnerable moment. Fantasies usually sound ridiculous, embarrassing, disgusting or plain horrible when judged by the light of ordinary conduct. It would be terrible (perhaps) to do them for real. We totally understand this in other areas of life: it could be lovely to read a novel about people stranded on an ice-floe in the arctic winter; though the reality would be horrendous. In a film, it might be deeply enjoyable to inhabit the lair of ruthless criminal; though in reality you are peaceable and law-abiding.

Other people's fantasies frequently sound a bit crazy - and so, of course, must our own. But odd though they can appear, sharing fantasies is central to our capacity for sexual excitement and closeness. They're not just an optional extra. They're part of what our partner needs to understand about us for us to be turned on (by which we really mean: to be intimate and loving).

13. One of the hardest things for anyone to understand about me is...

We end up lonely because there's something we feel is important about who we are that the other appears not to understand - and so, we can end up assuming, will never understand.

But this lack of understanding isn't usually because they are bad or uninterested. And it isn't irrevocable. It's just that there hasn't been a proper occasion to share things for a while. As relationships develop, we don't often get round to long, exploratory conversations, in which the more elusive parts of one another get properly explored. The feeling we know someone is the constant enemy of deepening and updating our knowledge of them.

Our partners know us well - but they can't magically intuit everything about us. We need to explain the big things that won't be obvious to them. We are changing all the time, and they are too. We're no longer who we were last year, and they aren't either.

Other people cannot read our minds. We're going to need to explain. And this is the moment when, at last, they will have the time to hear us.

14. I'm embarrassed to admit this, but I...

There are lots of things we do - which aren't necessarily terrible in themselves - but which we feel embarrassed or ashamed about. If we admit to them, we may look like fools and idiots. So we keep quiet. We try as best we can to present a more dignified and plausible front.

But let's allow for a moment of revelation:

-

I avoid going to a particular shop because I think one of the sales assistants looks down on me

-

I'd actually like to eat a whole packet of the chocolate biscuits you mocked in the supermarket

-

You know I said the cleaner accidentally broke your mug with the smiley face on it; actually it was me. I didn't mean to. I'm really sorry.

-

I particularly like it when you wear those kinds of shoes.

-

Increasingly, I get very anxious about not making it to the bathroom in time.

-

I find the national anthem uplifting.

-

I've always fancied buying a huge water pistol

Everyone is foolish in lots of ways. Admitting our own illnesses and quirks isn't designed to be humiliating. It doesn't take away from any of our real strengths and merits. Ideally, we discover that our partner isn't surprised, or that they knew already, or that they find these details (which we worried so deeply were ridiculous) actually rather endearing.

15. There are a few small things about you that drive me crazy...

Couples almost inevitably get maddened with each other around what look (on the surface) like absurdly small matters. An otherwise quite reasonable and decent person might admit that what drives them crazy about their partner includes: they press too hard on the chopping board; they don't put their seat belt on until after the car is started; in their handwriting 'b' and 'h' are practically indistinguishable; they think that there is a right and a wrong way to squeeze a toothpaste tube; they use the word the word 'tragic' to mean 'sad'; they leave drawers fractionally open; when they drink a glass of water they gulp it down and say 'ahh'.

Our reactions seem wildly out of proportion - even at times, to ourselves. We get very worked up and then feel crazy.

But rather than tell ourselves we are stupid to get worked up, we could, instead, try to give our partner a very calm and careful account of why this thing bothers us. This is useful because - of course - it's not the irritating detail itself that's troubling us. It's what it represents in our minds - which may indeed be worth a big discussion. The little things sit on top of large fears about the partner. That they may be callous or sloppy, rigid or sentimental...

But our partner can't know our fears. They can't know that indistinguishable letters (such a small issue!) stands for 'getting away with not trying'. Or that not putting the seatbelt on before starting (which we know really isn't a danger) upsets us because in our heads it suggests (however strange it sounds): 'I don't give a damn about authority'.

We're not justifying our irritation over tiny things: we're explaining our fears and thereby lessening their impact in the relationship.

16. What I probably need to be kindly teased for is...

Being gently teased can be one of the most enchanting things a partner can do for us. It signals both that they have spotted something about us that is a little excessive and worth pointing out, and that they are doing so in a way which is light-hearted, unanxious and sweet.

At the same time, acknowledging that there are aspects to our characters that we should be teased about signals that we realise that we are self-aware, and open to change. We might need to be teased for our attitudes to punctuality, for the way we over-explain stories, for our obsession with being in nature all the time, for our lack of intellectual interests, for our mania for museums...

At its best, teasing locates a tendency in us that's going a bit wrong and addresses it comically, rather than critically. It offers a gentle but firm corrective nudge. By laughing good-naturedly, we ourselves accept the justice of the point.

Teasing uses humour to take the sting out of criticism. Good teasing is always about something the person could quite easily change about themselves: eating too fast; checking one's phone out of habit (rather than urgent need) in social situations; leaping in too quickly when another person is speaking; a tendency on occasions to show off a little.

If we scan our own lives, we do probably notice some things about our own behaviour that we wouldn't mind being reminded not to do - if only the reminder was accompanied by a joke and a smile, rather than by a frown.

17. What would help me to change is if you..._

We want to change, but we can't do it alone. We need the other's help and for them to behave in particular ways towards us.

We're often reluctant to voice how we want to change, for fear that our partner will weigh in and try to 'help' us change in punitive and abrasive ways. They'll do so in a style that - we fear - will make things worse. They'll use our honesty against us. We imagine them nagging us or setting targets (which we'll fail to achieve) or telling other people 'how hard we're trying' - leaving us feeling humiliated and less able than ever to make the positive alterations we wish we could.

In saying there's something we'd like to change, we're not making a promise we can easily do it. We're showing that we're not indifferent to our own failings. This admission - almost on its own - is an important move. It shows our perception and intelligence about ourselves.

It's so much nicer to be with someone who is aware of their failings and tells us they wish they could overcome them - as opposed to with someone who seems to think they are just fine exactly as they are.

18. I could change X, if you changed Y..._

We often feel locked into behaviour we don't much like in ourselves because it feels like a necessary (if bad) response to things we don't much like in our partner.

It feels as if there's a horrible connection between what we admit is a bit nasty in us and what strikes us as a bit nasty about them. We get sullen - perhaps - because they are nagging; they are nagging because we are evasive and withdrawn; we get irritated because they are stubborn; they feel they have to dig in because we're so unreasonable.

One thing that can ideally happen is that we start to see more clearly how the way we are interacting is making things difficult for both of us. Instead of laying the blame on just one side, we admit that we are in an unfortunate dynamic, both of us creating and adding to the burden.

The solution is for both sides to become conscious of the dynamic and mutually to vow to do a little better going forward. It can be very tentative at first: if I go first and admit I can be rather awful in this way, can you join me and admit that you are just a little bit difficult in a corresponding area?

19. What I'm grateful to you for is...

Our partner has - of course - really helped us in some key ways. They made it possible to do things we'd never have accomplished on our own; they've comforted us at certain moments, they've maybe understood and been kind to difficult aspects of who we are; possibly they have saved us from the worst effects of certain tendencies in our nature. It's not always easy for us to come up with a list on the spur of the moment. That's partly because we're so familiar with the way we happen to be now and find it hard to hold onto a fully accurate picture of what we were like before we got together with them.

We naturally, though unfortunately, lose sight of the contribution they have made to our lives. And - of course - that contribution typically gets swamped by our awareness of the ways in which they're not currently helping us as much as we'd like.

One of the odd things about gratitude is that it may be directed towards people and things that were rather unpleasant at the time. We might - in retrospect - be grateful to a teacher at school who pushed us hard to perform better. Similarly, we can be not only grateful for ways our partner has been nice to us, but also for ways they've been good for us.

We need to jog our own memories and help each other come to a fairer, more precise view of our lives together.

20.__What I'd miss so much about you is...

Suppose - without being morbid or brutal - you weren't to see your partner again. And you could look back from a distance and think about your relationship. What would you miss.

Imagine any hurt or shame has faded sufficiently and you can afford to admit there are things you really would miss enormously about them. What would be they be? We don't naturally carry such a list around with us at the front of our minds. It takes time to properly identify the things we'd ache for and be very sorry we had lost. There would, definitely, be plenty. Because this is always what happens. If you leave a country you've grown sick of, eventually you realise there were things about it you really regret - and which you didn't properly appreciate at the time.

Instead of waiting for the passage of time, we can in imagination propel ourselves into a possible future and - from there - try to think what we'd feel. The point is not so much to predict what we might miss as to get us to see that those things are - of course - in our grasp right now. Here are some suggestions:

-

When you were so nice and engaging with that awkward person

-

When you laugh so openly at a very silly joke

-

Your intent face when you are watching television

-

When you are playing with the children and saying good night to them

-

When you get embarrassed about not knowing any geographical facts (one time you confused Greenland and Alaska)

Each of these moments is a trigger for a wider set of thoughts and feelings: their kindness, their innocence, their endearing silliness, their vulnerability, their moments of great gentleness, humility and generosity. Which are all entirely true and sit alongside everything else - waiting to be noticed and properly loved.

21. What I'd love you to remember about me is...

We're not actually anticipating leaving the relationship or an early exit from life. Instead, we're trying to rehearse some of the nobler and more lovely things about ourselves.

We might want to draw attention to our best intentions (even when they didn't entirely work out); to the sweeter aspects of our character (even though they haven't always been on display); or to the good things about us which (unfortunately) haven't always made the relationship harmonious: our sensitivity, our devotion to work, perhaps our honesty (though it's been painful at times) or our politeness (though at times, it seemed to make us evasive).

Ostensibly, the recipient of this self-spoken eulogy is one's partner. But the deeper audience is oneself. It's not that we're in danger of thinking we're just wonderful and will be remembered with the deepest love and admiration. Our fears are pretty much the opposite. What we're doing is reminding ourselves that in fact we are (in some ways) very decent and well-intentioned participants in this relationship; that we really do want our partner to love us - and that (below the surface perhaps), we long to deserve their love.

22. If this was our very first date, I'd ...

The idea of starting afresh is often very tempting: if only we could put aside the past hurts and frustrations and begin again with the wisdom we now have. We know now so much more about ourselves and about being in a relationship than we did when the two of us had our first date. How would you now behave?

You might - for instance - feel that it would be important to explain more fully about certain aspects of yourself. You might want to be more upfront and admit that you are quite difficult in certain ways - so that there wouldn't be a gradual unfolding of frustration and disappointment. Perhaps in this fantasised new first date you'd be interested in getting to know quite different things about your partner. You'd maybe want to learn a lot more about their childhood (and especially it's difficult parts - not just the happy memories).

But, perhaps also, you might want to be much nicer and sweeter than you normally are. You might want to charm your partner, listen very carefully to their ideas and opinions; you might be intrigued afresh by the way they fold their hands under their chin or by the ironic way they shrug their shoulders when telling a funny story. You'd be re-sensitized to a range of endearing qualities that - very understandably - get neglected in daily life.

The first date thought-experiment gets us to see our partner afresh; and what we're seeing is - of course - part of who they really are. We're using an artifice to correct the blindness that comes from being very close to another person for a very long time.

This article was originally published on The School of Life. It has been republished here with permission.